Park Chung Hee was the single most influential figure in South Korean politics during the twentieth century. He ruled the Republic of Korea from 1961 to 1979, leading the country through a period of rapid economic development and transforming South Korean society. At the same time, Park left a highly controversial legacy due to the highly authoritarian manner in which he governed.

Park was born in 1917 into a poor yangban family but he was ambitious and eager to seize whatever opportunities could be found while South Korea remained under Japanese colonial rule. Park attended a teacher’s college and worked briefly as an elementary school before deciding to pursue a military career. Park first passed the test for the Japanese-run Manchurian Military Academy. His talents as an officer were swiftly recognized and he was one of the few Koreans allowed to attend the Japanese Imperial Military Academy near Tokyo. He was subsequently posted to a Japanese Army regiment in Manchuria and served there until Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II.

Park returned to South Korea when it was still under American occupation. He was one of the first members of the constabulary, an indigenous military force supervised by the U.S. Army Military Government in Korea. Park’s political orientation during this period was unclear, however. He was known to be close to some members of the Korean Worker’s Party who had infiltrated the constabulary. In 1948, Park was nearly executed after an attempted mutiny in the organization led to a purge of leftists from its ranks. The future president’s superior officers pleaded with the Rhee government to spare his life on the basis of his strong potential as a military officer.

Park proved both his potential and his loyalty to the ROK during the Korean War. After the war began he was reinstated as an active service officer in the South Korean Army and gradually rose in its ranks. By the time the war ended Park had been appointed a brigadier general and earned a reputation as one of the most promising young officers in the army.

Like some of the other young officers in the ROK Army during the 1950s, Park felt some measure of frustration with civilian rule. Syngman Rhee, who dominated South Korean politics until 1960, was an aging autocrat whose corrupt government did little to raise living standards or improve the South Korean economy. Chang Myon, who became prime minister in 1960 after a student-led uprising led to Rhee’s ouster, had difficulty controlling the forces that had put him in power. Disorder prevailed and the ROK’s economic situation did not improve.

Frustrated with the prevailing situation in South Korea, Park conspired with other military officers to form a junta, which came to be known as the Military Revolutionary Committee, and began planning a coup. Park’s committee seized power on 16 May 1961 and shortly thereafter announced the formation of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (SCNR), of which Park was the chairman.

Park would remain in control of South Korean politics until 1979. His tenure in power can generally be divided into three phases. During the first phase, which lasted until 1963, Park governed through the SCNR. Under pressure from the United States, Park allowed a presidential election in 1963 in which he managed to narrowly defeat his opponent. Between 1963 and 1972, Park governed South Korea through a government that was formally democratic but limited dissent and participation. In 1972, however, Park suddenly decided to abandon democratic institutions, abolished the South Korean constitution and announced the establishment of Yusin—a new system of harsh, authoritarian rule.

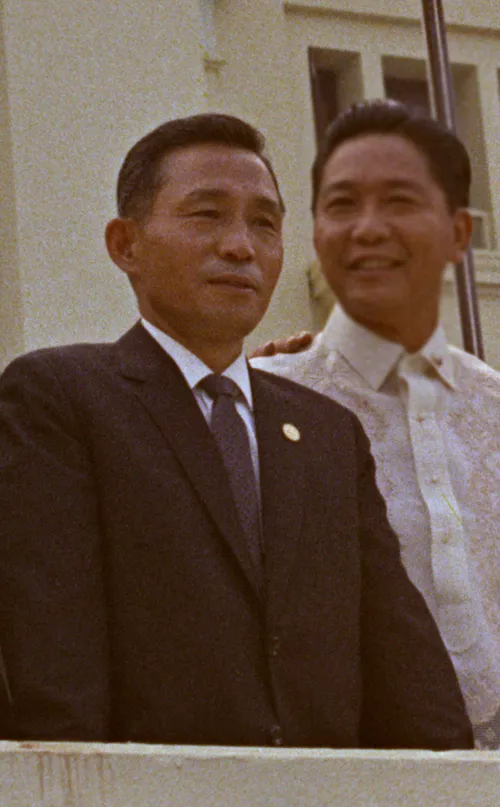

The first of these phases was marked by the SCNR’s rapid consolidation of power and sweeping political and economic reforms. In November 1961, Park Chung Hee visited the United States and was successful in reassuring the Kennedy administration that he was committed to containing communism, developing the economy, and, eventually, holding free elections. By the time Park ran for the presidency in 1963, he had already created three key institutions that would be the backbone of his tenure in power: the Economic Planning Board (EPB), which Park entrusted with setting a course for Korea’s economic development; the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), which Park used to intimidate and control his opposition; and the Democratic Republican Party (DRP), which Park used to fill the government with his allies and manage electoral politics.

After Park triumphed in the 1963 presidential election, he began taking a variety of unpopular but necessary measures to promote rapid economic development. These included: normalizing relations with Korea’s former colonizer Japan in 1965, raising interest rates, and improving tax collection. Under Park’s leadership, South Korea developed an export driven model of economic growth wherein special incentives were provided to large business conglomerates (the chaebŏl) in the form of preferential loans to manufacture goods for sale abroad. South Korea’s economy began to take off regularly achieving double-digit growth rates by the mid 1960s.

During the late 1960s, Park began to move toward greater authoritarianism. There were several reasons for this: North Korea’s growing adventurism, fear that the United States would reduce its security commitment to South Korea under the Nixon Doctrine, the need to suppress labor while promoting rapid industrialization, and the growing popularity of Park’s political opponents, especially Kim Dae Jung. In 1972, Park suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and made himself president for life. He used his new powers to brutally punish dissenters while pushing the economy into heavy industry. It was during this period that South Korea moved toward economic maturity, beginning to manufacture steel, ships, automobiles and other electronics. Despite the achievements of Park’s economic statecraft, by the late 1970s South Korea was racked by growing protests against his authoritarianism.

It was in the midst of violent protests against the Yusin system that Park was assassinated in October 1979. By the end of the month massive demonstrations had spread across the southeastern cities of Pusan and Masan. In a meeting with KCIA Director, Kim Chaegyu, an argument broke out between Kim and Park with Park criticizing the KCIA for not doing enough to end the demonstrations. Frustrated with the criticism, Kim fired a pistol at Park and his bodyguard Cha Jichŏl, killing both.

Park’s legacy is a complicated one. In South Korea, the left has remained critical of the former president arguing that the Yusin system and the repressive nature of his government significantly impeded democratization. Yet Park continues to be admired by many South Koreans for his role in creating the “Miracle on the Han”—so much so that that his daughter, Park Geun Hye, launched a highly successful political career and was elected the ROK’s first female president, in part by drawing on her father’s enduring reputation for being the man who pulled South Korea out of poverty.