d'Vinci

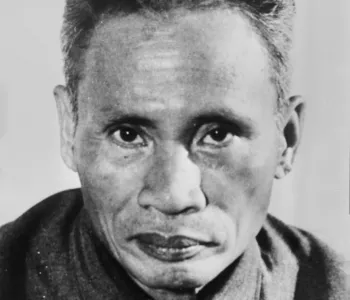

Marshall, George C. (George Catlett) 1880- 1959

George C. Marshall was a key military figure during WWII, and the period directly following it.

b. December 31, 1880 - d. October 16, 1959

George C. Marshall was a key military figure during WWII, and the period directly following it. Marshall was involved in the reconstruction of Europe, and formed the "Marshall Plan" to help devastated western Europe get back on its feet.

Army Chief of Staff, 1939-1945; Special Envoy to China, 1945-1947; Secretary of State, 1947-1949; Defense Secretary, 1950-1951

George C. Marshall was a key military figure during WWII, and the period directly following it. Marshall was involved in the reconstruction of Europe, and formed the "Marshall Plan" to help devastated western Europe get back on its feet.

Army Chief of Staff, 1939-1945; Special Envoy to China, 1945-1947; Secretary of State, 1947-1949; Defense Secretary, 1950-1951

Marshall was born on December 31, 1880, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

His father owned a prosperous coal business in Pennsylvania, but the boy, deciding to become a soldier. He enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute, from which he graduated in 1901 as senior first captain of the Corps of Cadets.

After serving in posts in the Philippines and the United States, Marshall graduated with honors from the Infantry-Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth in 1907, and from the Army Staff College in 1908. The young officer distinguished himself in a variety of posts in the next nine years, earning an appointment to the General Staff in World War I and sailing to France with the First Division. After acting as aide-de-camp to General Pershing from 1919 to 1924, Marshall served in China from 1924 to 1927, and then successively as instructor in the Army War College in 1927, as assistant commandant of the Infantry School from 1927 to 1932, as commander of the Eighth Infantry in 1933, as senior instructor to the Illinois National Guard from 1933 to 1936, and as commander, with the rank of brigadier general, of the Fifth Infantry Brigade from 1936 to 1938.*

In 1938, he became chief of the Department of War's Plans Division. He was nominated Army chief of staff by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and sworn in on September 1, 1939. He directed the American military buildup for World War II by raising new divisions, training troops, procuring weapons and equipment, and selecting top commanders. The Army grew from fewer than 200,000 men to a fighting force of more than 8 million men by 1942.

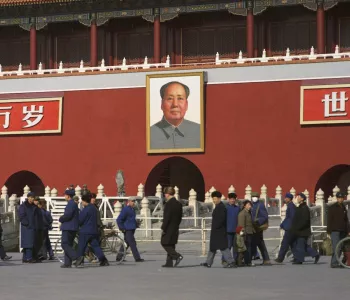

After fighting ended in World War II, Marshall resigned on November 21, 1945, at the age of 65, but was asked by the President that year to go to China as his special envoy with the rank of ambassador to negotiate a settlement in the Chinese civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists. He failed in his efforts, but was nominated by President Harry Truman as Secretary of State. On January 8, 1947, the U.S. Senate disregarded precedent and unanimously approved the nomination without a hearing, making Marshall the first military commander ever to lead the U.S. Department of State.

Dubbed the "organizer of victory" by Winston Churchill for his World War II leadership, George Marshall is perhaps best known for his postwar plan to rebuild Europe that bears his name. In a famous Harvard commencement address on June 5, 1947, Marshall outlined American ideas for European recovery that became known as the Marshall Plan. As Secretary of State he oversaw the provision of aid to Greece and Turkey, the recognition of Israel and the initial discussions that led to NATO.

In August 1950, Truman again persuaded him to come out of retirement to replace Defense Secretary Louis Johnson, who was forced to resign on September 12, 1950, as a result of U.S. reverses and lack of military preparedness in the early days of the war in Korea. There was a fierce congressional fight over Marshall’s confirmation as a result of hysteria over the 1949 Communist victory in China. Marshall met these personal attacks, and all others, with calm logic.

As Secretary of Defense, Marshall’s top priority was more manpower for the armed forces to meet the demands of both Korea and Europe while maintaining an adequate reserve. He secured the appointment of Anna M. Rosenberg as Assistant Secretary of Defense for manpower and brought a major civilian architect of U.S. airpower, Robert A. Lovett, back into government service as Deputy Secretary of Defense.

Marshall also restored harmony between the Defense and State Departments. Early on he established a good working relationship with the military chiefs. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), General Omar N. Bradley, had served under him in World War II, and the two men worked well together, as was the case with Bradley’s successor, General J. Lawton Collins. Marshall also respected and worked well with Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest P. Sherman.

Marshall played a major role in the development of tensions in Korea, and the events that unfolded in the attempt to prevent a communist takeover of the South. The Inchon landing and the Pusan Perimeter breakout preceded Marshall’s confirmation as Secretary of Defense, but he participated in the decision authorizing MacArthur to conduct operations north of the 38th Parallel. Marshall shared the view of MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs that he should follow up his victory. A secret “eyes only” signal from Marshall to MacArthur on September 29 declared Washington’s commitment to an advance into North Korea (“We want you to feel unhampered strategically and tactically to proceed north of the 38th Parallel”), but he advised against advance announcements which might precipitate a new vote in the United Nations.

For some time the top figures in the Truman administration had worried about a clash with China. Despite MacArthur’s unbridled confidence at the Wake Island meeting with Truman on October 15, the Chinese had already begun to move forces into Korea. After the initial Chinese military clashes with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and American units at the end of October, neither Marshall nor the Joint Chiefs made any effort to halt MacArthur’s advance. Marshall opposed MacArthur’s request for permission to bomb the Yalu bridges unless the security of all his forces was directly threatened. When MacArthur predicted dire results, Truman authorized the strike. Marshall supported the recommendation from the Joint Chiefs authorizing pursuit of enemy aircraft into Manchurian airspace, but Allied reaction caused the proposal to be dropped. Marshall and the Joint Chiefs were generally supportive of MacArthur because of the traditional Pentagon reluctance to supervise field commanders too closely and the fact that MacArthur was no ordinary commander.

Following the second, and massive, Chinese military intervention in late November, Marshall and the Joint Chiefs sought ways to help the General. At the meeting of the National Security Council on November 28, Marshall agreed with the President and the Joint Chiefs that all-out war with China must be avoided. The United States should continue to work through the United Nations (U.N.) and maintain U. N. support for the war. When the JCS instructed MacArthur to withdraw X Corps from its exposed position, Marshall inserted a statement that the region northeast of the waist of Korea was to be avoided except for military operations essential to protect U.N. military security.

In the debate over what to do about the changed military situation in Korea, Marshall opposed a cease–fire with the Chinese, because it would represent a “great weakness on our part,” and added that the United States could not in “all good conscience” abandon the South Koreans. When British Prime Minister Clement Attlee suggested negotiations with the Chinese, Marshall expressed opposition, arguing that it was almost impossible to negotiate with the Chinese Communists; he also expressed fear of the effects on Japan and the Philippines of concessions to the Communists. At the same time Marshall sought ways to avoid a wider war with China. When many in Congress favored an expanded war, Marshall was among the administration leaders who, in February 1951, stressed the paramount importance to the United States of Western Europe.

In the April 6 meeting between Truman and his closest advisors to discuss the future of MacArthur, Marshall characteristically urged caution. If MacArthur were recalled, military appropriations might be obstructed by Congress. Later that morning Truman asked Marshall to review all the messages between Washington and Tokyo over the past two years. When the five men met again the next morning, Marshall declared that, having read the papers, he now shared W. Averell Harriman's view that MacArthur should have been dismissed two years earlier for flouting administration directives over occupation policies for Japan. Marshall and the other men involved in the decision to fire MacArthur exhibited a considerable degree of courage given the political risks involved.

In the congressional hearings which followed the General’s dismissal, Marshall defended the decision. Long-time rivals, in many ways Marshall and MacArthur represented different viewpoints: moderate conservative versus committed right-winger, Europe-first versus concentration on Asia, and limited war versus total war. Marshall defended the concept of limited war in Korea; he hoped it would “remain limited.” He said there was no easy solution to the Cold War short of another world war, the cost of which would be “beyond calculation,” now that the Soviet Union possessed the atomic bomb. As a result, the administration’s policy remained that of containing communist aggression by different methods in different areas without resorting to total war. Such a policy was not always easy or popular. But the Western alliance would be kept intact, America would rearm as quickly as possible, the status quo would be maintained, and Formosa (Taiwan) would “never be allowed” to come under communist control.

By now the Truman administration was under heavy attack. In June 1951, when Senator Joseph McCarthy demanded the resignations of Acheson and Marshall and threatened Truman with impeachment, he all but called Marshall a communist. The unjust attacks against him may well have confirmed Marshall’s decision to step down from a position he had agreed to hold only for six months to a year. McCarthy’s attack practically ended Marshall’s usefulness as a nonpartisan member of the administration. At Truman’s request he stayed on until September 1, 1951, when he officially resigned. He was replaced by his deputy, Lovett. For Marshall it was the end of fifty years of dedicated government service.

Apart from his other services, as Secretary of Defense, Marshall had restored morale in the Armed Forces, rebuilt a cordial relationship between the Defense and State departments, increased the size of the military, and assisted Truman in the crisis over the MacArthur firing. These were not inconsiderable achievements, and Marshall’s status has grown steadily since the 1950s among historians and the military both in the U.S. and the United Kingdom.

In 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He died in Washington, D.C., in 1959 at age 78 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

*from the Nobel Prize

His father owned a prosperous coal business in Pennsylvania, but the boy, deciding to become a soldier. He enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute, from which he graduated in 1901 as senior first captain of the Corps of Cadets.

After serving in posts in the Philippines and the United States, Marshall graduated with honors from the Infantry-Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth in 1907, and from the Army Staff College in 1908. The young officer distinguished himself in a variety of posts in the next nine years, earning an appointment to the General Staff in World War I and sailing to France with the First Division. After acting as aide-de-camp to General Pershing from 1919 to 1924, Marshall served in China from 1924 to 1927, and then successively as instructor in the Army War College in 1927, as assistant commandant of the Infantry School from 1927 to 1932, as commander of the Eighth Infantry in 1933, as senior instructor to the Illinois National Guard from 1933 to 1936, and as commander, with the rank of brigadier general, of the Fifth Infantry Brigade from 1936 to 1938.*

In 1938, he became chief of the Department of War's Plans Division. He was nominated Army chief of staff by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and sworn in on September 1, 1939. He directed the American military buildup for World War II by raising new divisions, training troops, procuring weapons and equipment, and selecting top commanders. The Army grew from fewer than 200,000 men to a fighting force of more than 8 million men by 1942.

After fighting ended in World War II, Marshall resigned on November 21, 1945, at the age of 65, but was asked by the President that year to go to China as his special envoy with the rank of ambassador to negotiate a settlement in the Chinese civil war between the Nationalists and the Communists. He failed in his efforts, but was nominated by President Harry Truman as Secretary of State. On January 8, 1947, the U.S. Senate disregarded precedent and unanimously approved the nomination without a hearing, making Marshall the first military commander ever to lead the U.S. Department of State.

Dubbed the "organizer of victory" by Winston Churchill for his World War II leadership, George Marshall is perhaps best known for his postwar plan to rebuild Europe that bears his name. In a famous Harvard commencement address on June 5, 1947, Marshall outlined American ideas for European recovery that became known as the Marshall Plan. As Secretary of State he oversaw the provision of aid to Greece and Turkey, the recognition of Israel and the initial discussions that led to NATO.

In August 1950, Truman again persuaded him to come out of retirement to replace Defense Secretary Louis Johnson, who was forced to resign on September 12, 1950, as a result of U.S. reverses and lack of military preparedness in the early days of the war in Korea. There was a fierce congressional fight over Marshall’s confirmation as a result of hysteria over the 1949 Communist victory in China. Marshall met these personal attacks, and all others, with calm logic.

As Secretary of Defense, Marshall’s top priority was more manpower for the armed forces to meet the demands of both Korea and Europe while maintaining an adequate reserve. He secured the appointment of Anna M. Rosenberg as Assistant Secretary of Defense for manpower and brought a major civilian architect of U.S. airpower, Robert A. Lovett, back into government service as Deputy Secretary of Defense.

Marshall also restored harmony between the Defense and State Departments. Early on he established a good working relationship with the military chiefs. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), General Omar N. Bradley, had served under him in World War II, and the two men worked well together, as was the case with Bradley’s successor, General J. Lawton Collins. Marshall also respected and worked well with Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest P. Sherman.

Marshall played a major role in the development of tensions in Korea, and the events that unfolded in the attempt to prevent a communist takeover of the South. The Inchon landing and the Pusan Perimeter breakout preceded Marshall’s confirmation as Secretary of Defense, but he participated in the decision authorizing MacArthur to conduct operations north of the 38th Parallel. Marshall shared the view of MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs that he should follow up his victory. A secret “eyes only” signal from Marshall to MacArthur on September 29 declared Washington’s commitment to an advance into North Korea (“We want you to feel unhampered strategically and tactically to proceed north of the 38th Parallel”), but he advised against advance announcements which might precipitate a new vote in the United Nations.

For some time the top figures in the Truman administration had worried about a clash with China. Despite MacArthur’s unbridled confidence at the Wake Island meeting with Truman on October 15, the Chinese had already begun to move forces into Korea. After the initial Chinese military clashes with the Republic of Korea (ROK) and American units at the end of October, neither Marshall nor the Joint Chiefs made any effort to halt MacArthur’s advance. Marshall opposed MacArthur’s request for permission to bomb the Yalu bridges unless the security of all his forces was directly threatened. When MacArthur predicted dire results, Truman authorized the strike. Marshall supported the recommendation from the Joint Chiefs authorizing pursuit of enemy aircraft into Manchurian airspace, but Allied reaction caused the proposal to be dropped. Marshall and the Joint Chiefs were generally supportive of MacArthur because of the traditional Pentagon reluctance to supervise field commanders too closely and the fact that MacArthur was no ordinary commander.

Following the second, and massive, Chinese military intervention in late November, Marshall and the Joint Chiefs sought ways to help the General. At the meeting of the National Security Council on November 28, Marshall agreed with the President and the Joint Chiefs that all-out war with China must be avoided. The United States should continue to work through the United Nations (U.N.) and maintain U. N. support for the war. When the JCS instructed MacArthur to withdraw X Corps from its exposed position, Marshall inserted a statement that the region northeast of the waist of Korea was to be avoided except for military operations essential to protect U.N. military security.

In the debate over what to do about the changed military situation in Korea, Marshall opposed a cease–fire with the Chinese, because it would represent a “great weakness on our part,” and added that the United States could not in “all good conscience” abandon the South Koreans. When British Prime Minister Clement Attlee suggested negotiations with the Chinese, Marshall expressed opposition, arguing that it was almost impossible to negotiate with the Chinese Communists; he also expressed fear of the effects on Japan and the Philippines of concessions to the Communists. At the same time Marshall sought ways to avoid a wider war with China. When many in Congress favored an expanded war, Marshall was among the administration leaders who, in February 1951, stressed the paramount importance to the United States of Western Europe.

In the April 6 meeting between Truman and his closest advisors to discuss the future of MacArthur, Marshall characteristically urged caution. If MacArthur were recalled, military appropriations might be obstructed by Congress. Later that morning Truman asked Marshall to review all the messages between Washington and Tokyo over the past two years. When the five men met again the next morning, Marshall declared that, having read the papers, he now shared W. Averell Harriman's view that MacArthur should have been dismissed two years earlier for flouting administration directives over occupation policies for Japan. Marshall and the other men involved in the decision to fire MacArthur exhibited a considerable degree of courage given the political risks involved.

In the congressional hearings which followed the General’s dismissal, Marshall defended the decision. Long-time rivals, in many ways Marshall and MacArthur represented different viewpoints: moderate conservative versus committed right-winger, Europe-first versus concentration on Asia, and limited war versus total war. Marshall defended the concept of limited war in Korea; he hoped it would “remain limited.” He said there was no easy solution to the Cold War short of another world war, the cost of which would be “beyond calculation,” now that the Soviet Union possessed the atomic bomb. As a result, the administration’s policy remained that of containing communist aggression by different methods in different areas without resorting to total war. Such a policy was not always easy or popular. But the Western alliance would be kept intact, America would rearm as quickly as possible, the status quo would be maintained, and Formosa (Taiwan) would “never be allowed” to come under communist control.

By now the Truman administration was under heavy attack. In June 1951, when Senator Joseph McCarthy demanded the resignations of Acheson and Marshall and threatened Truman with impeachment, he all but called Marshall a communist. The unjust attacks against him may well have confirmed Marshall’s decision to step down from a position he had agreed to hold only for six months to a year. McCarthy’s attack practically ended Marshall’s usefulness as a nonpartisan member of the administration. At Truman’s request he stayed on until September 1, 1951, when he officially resigned. He was replaced by his deputy, Lovett. For Marshall it was the end of fifty years of dedicated government service.

Apart from his other services, as Secretary of Defense, Marshall had restored morale in the Armed Forces, rebuilt a cordial relationship between the Defense and State departments, increased the size of the military, and assisted Truman in the crisis over the MacArthur firing. These were not inconsiderable achievements, and Marshall’s status has grown steadily since the 1950s among historians and the military both in the U.S. and the United Kingdom.

In 1953 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He died in Washington, D.C., in 1959 at age 78 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

*from the Nobel Prize