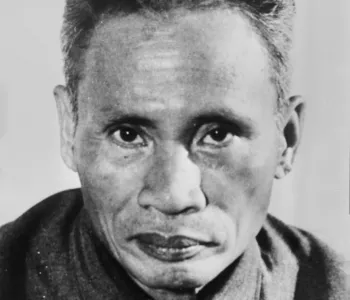

Ho Chin Minh, founder and leader of the Vietnamese communist movement and president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam from 1945 until his death in 1969. He was born Nguyen Sinh Cung on 19 May 1890 in Nghe An Province in central Vietnam. After receiving his initial education from his father and at a village school, Ho studied at the Lycee Quoc-Hoc in the old imperial capital of Hue. It was a school designed to perpetuate Vietnamese nationalist traditions.

In 1912 he went to France, where he worked at many odd jobs and became active in socialist politics and as an advocate of Indochinese independence. During World War I he visited the United States. At the Versailles peace conference, he petitioned the delegates on behalf of Vietnamese self-determination but was ignored. In 1920 Ho became a founding member of the French Communist Party.

After spending several years at sea, Ho settled in London during World War I; there he worked in a restaurant and was first exposed to Marxist ideas. Moving to Paris, he adopted the pseudonym Nguyen Ai Quoc (Nguyen the Patriot) and first came to public attention when he presented a petition to the Versailles Peace Conference demanding independence for Vietnam in accordance with the principle of self-determination. He also because active in radical circles and in 1920 became a founding member of the French Communist Party. During the next three years he worked actively among radical exile groups from the colonies who were living in France, participating in an Intercolonial Union formed under Communist sponsorship and publishing an anticolonial journal, Le Paria (The Pariah).

He went to Moscow in 1922, joined the Comintern and met with Lenin. In 1925 he went to China to work for the Soviet mission with Chiang Kai-Shek's government. After Chiang turned on the communists in 1927, Ho fled to Moscow. During the 1930s he founded the Indochinese Communist Party, studied in Moscow and fought alongside Mao. In 1940 he returned to Vietnam. He founded the Viet Minh, the League for the Independence of Vietnam.

In 1923 Ho was summoned to Moscow, where he studied Marxist doctrine and worked at Comintern headquarters. Already identified as a vigorous spokesman for the anticolonial cause, he served as a delegate with the Peasant International and urged the Communist International to take the lead in promoting revolution in Asia. In late 1924 he was sent to Canton as an interpreter for the Comintern mission to the revolutionary government of Sun Yatsen. His real assignment was to establish a communist movement in French Indochina. Within months Ho recruited radical Vietnamese patriots living in exile in South China into a new revolutionary organization, the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth League. In conformity with prevailing Leninist theory and Ho's own proclivities, the league's program combined social revolution with nationalism and soon became a leading force within patriotic circles in Vietnam.

In the spring of 1927 Ho was forced to leave Canton because of Chiang Kai-shek's crackdown on local Communists. He spent the next three years in Europe and in Siam, where he recruited within the Vietnamese exile community living in the provinces. In early 1930 he returned to South China to resolve a factional squabble within the league and, at a meeting held in Hong Kong, presided over the formation of a formal Communist Party. He remained in Hong Kong as liaison officer for the Comintern's Far Eastern Bureau and was imprisoned by British authorities in 1931. Released in 1933 as a result of pleas by a British civil rights organization, he went to Moscow and spent the next several years in the Soviet Union, reportedly recovering from tuberculosis. There were rumors that he was in Stalin's disfavor because of his nationalist views, but in August 1935 he attended the Seventh Comintern Congress.

In 1938 Ho went to China, where he briefly visited Chinese Communist headquarters in Yan'an and then served as a guerrilla training instructor in central China. In the summer of 1940, with war approaching, he returned to South China and established contact with leading members of the Indochinese Communist Party. The following May, with most of Vietnam under Japanese occupation he chaired a meeting of the Central Committee just inside the Vietnamese border. It announced the formation of the League for the Independence of Vietnam (Viet Minh for short), a new front organized under Party leadership to seek independence from French rule and Japanese military occupation. During the next few years--interrupted by another stint in a Chinese prison--Ho led the Party in seeking popular support for the Viet Minh front and building up its guerrilla forces for an uprising at the close of the war.

In August 1945, Viet Minh forces launched an insurrection to seize power throughout Vietnam. Hanoi was occupied with little resistance, and in early September a Democratic Republic of Vietnam was created, with Ho Chi Minh—in his first public use of the name—as president. For the next several months Ho attempted to broaden the popular base of the new government while seeking a negotiated settlement with France. Politically astute and conciliatory, he managed to reduce the distrust of rival nationalist leaders and reached agreement on a coalition cabinet at the end of the year. Early in 1946 a National Assembly was elected and confirmed him as president. In the meantime, protracted negotiations with the French representative in Indochina resulted in a preliminary agreement calling for the creation of a Vietnamese "free state" within the French Union. Both achievements, however, were short lived. In the summer of 1946, the tenuous alliance between the Viet Minh and the nationalists broke down, and the latter were driven out of the government. Meanwhile, negotiations with the French foundered when they retreated from the terms of the preliminary agreement. In September, despite the misgivings of Party colleagues, Ho signed a modus vivendi in Paris, but on his return to Hanoi, tensions between Vietnamese and French forces escalated, and in December war broke out.

On September 2, 1945, Ho and his league declared Vietnamese independence. When the French colonial rulers tried to reassert their authority, Ho settled for nominal autonomy as a member of the French Union. The French-Vietnamese truce broke in late 1946, initiating a war that ended in 1954 with the Vietnamese victory at Dien Bien Phu. At the following Geneva conference, Ho allowed his Chinese and Soviet friends to pressure him into a highly unsatisfactory compromise that divided Vietnam in two. From that time Ho's primary goal was the reunification of Vietnam. He pursued this particularly through support of the Viet Cong guerrillas fighting the Southern government. Even though South Vietnam received ever-increasing support from the United States (which after 1964 began to bomb the North), Ho remained confident of victory and rejected negotiations with Washington. Only in 1968, after the U.S. bombardments of North Vietnam stopped in the wake of the Tet Offensive, did his government agree to talks. Shortly after this turning point in the war, Ho died of a heart attack at the age of 79 on September 3, 1969.

During the next several years, Viet Minh forces retreated to the hills and fought against French forces in the lowlands. By 1954, the French had wearied of the war and sought a negotiated settlement. Once again, militant elements in the Party resisted a compromise, but Ho used his formidable influence to gain the approval of his colleagues, and in July an agreement was reached calling for a truce and a temporary division of Vietnam into a communist north and a noncommunist south.

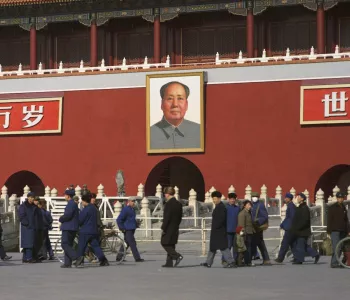

After 1954, Ho Chi Minh remained president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and chairman of the Party but gradually turned over day-to-day responsibilities to trusted lieutenants such as Pham Van Dong, Truong Chinh, and Le Duan. He played a symbolic role as head of state and as a mediator of Party disputes and was active on the international scene, where he promoted Vietnamese national interests within the socialist bloc and attempted to prevent the widening split between Moscow and Beijing. Convinced of the importance of Soviet friendship, he was also sensitive to the brooding presence of China and attempted to maintain cordial relations with the leaders of both communist states. During the 1960s, he appeared to decline in health and his role was reduced to occasional public appearances. He died of an apparent heart attack on 3 September 1969, at the age of seventy-nine.

Ho Chi Minh's importance to modern Vietnam can hardly be exaggerated. He was not only the founder of the Communist Party but also its recognized leader during most of its first half-century of existence. He provided it with ideological guidance, international prestige, a tradition of internal unity, and a sense of realism that on many occasions enabled it to triumph over adversity. Today he remains the symbol of the nation. His memory is enshrined in a mausoleum in Hanoi and in a new name for Saigon—Ho Chi Minh City.