Robert Strange McNamara was born in San Francisco where his father was sales manager of a wholesale shoe firm. He later said he had aspired to a Stanford University education, but could not afford it; he graduated in 1937 from the University of California, Berkeley with a degree in economics and philosophy, earned a master's degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration in 1939, worked a year for the accounting firm of Price Waterhouse in San Francisco, and then in August 1940 returned to Harvard to teach in the business school. Following his involvement there in a program to teach the analytical approaches used in business to officers of the Army Air Force, he entered the Army as a captain in early 1943, served under Col. Curtis LeMay with analysis of U.S. bombers' efficiency and effectiveness as a major responsibility, and left active duty three years later with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

In 1946 McNamara joined Ford Motor Company, which he later said had been the result of a Life magazine article saying how few college-educated managers there were at the then unprofitable company. He started there as manager of planning and financial analysis. He advanced rapidly through a series of top-level management positions, becoming on 9 November 1960 the first president of Ford from outside the family of Henry Ford, one day after President Kennedy's election. McNamara received substantial credit for Ford's expansion and success in the postwar period.

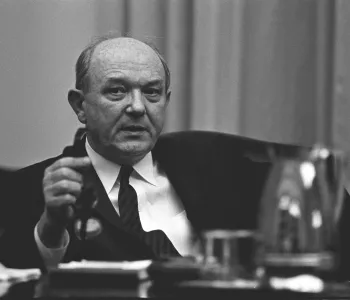

President-elect John F. Kennedy, very much concerned with defense matters although lacking Eisenhower's mastery of the issues, first offered the post of secretary of defense to former secretary Robert A. Lovett. Lovett declined but recommended McNamara; Kennedy had him approached by Sargent Shriver (regarding either the Treasury or the Defense cabinet post), and less than five weeks after becoming president at Ford Motors, McNamara accepted Kennedy's invitation to serve as Secretary of Defense.

Although not especially knowledgeable about defense matters, McNamara immersed himself in the subject, learned quickly, and soon began to apply an "active role" management philosophy, in his own words "providing aggressive leadership questioning, suggesting alternatives, proposing objectives and stimulating progress." He rejected radical organizational changes, such as those proposed by a group Kennedy appointed, headed by Sen. W. Stuart Symington, which would have abolished the military departments, replaced the Joint Chiefs of Staff with a single chief of staff, and established three functional unified commands. McNamara accepted the need for separate services but argued that "at the end we must have one defense policy, not three conflicting defense policies. And it is the job of the Secretary and his staff to make sure that this is the case."

Initially the basic policies outlined by President Kennedy in a message to Congress on March 28, 1961 guided McNamara in the reorientation of the defense program. Kennedy rejected the concept of first-strike attack and emphasized the need for adequate strategic arms and defense to deter nuclear attack on the United States and its allies. U.S. arms, he maintained, must constantly be under civilian command and control, and the nation's defense posture had to be "designed to reduce the danger of irrational or unpremeditated general war." The primary mission of U.S. overseas forces, in cooperation with allies, was "to prevent the steady erosion of the Free World through limited wars." Kennedy and McNamara rejected massive retaliation for a posture of flexible response. The United States wanted choices in an emergency other than "inglorious retreat or unlimited retaliation," as the president put it. Out of a major review of the military challenges confronting the United States initiated by McNamara in 1961 came a decision to increase the nation's limited warfare capabilities. These moves were significant because McNamara was abandoning Eisenhower's policy of massive retaliation in favor of a flexible response strategy that relied on increased U.S. capacity to conduct limited, non-nuclear warfare.

The Vietnam conflict came to claim most of McNamara's time and energy. The Truman and Eisenhower administrations had committed the United States to support the French and native anti-Communist forces in Vietnam in resisting efforts by the Communists in the North to control the country. The U.S. role, including financial support and military advice, expanded after 1954 when the French withdrew. During the Kennedy administration, the U.S. military advisory group in South Vietnam steadily increased, with McNamara's concurrence, from just a few hundred to about 17,000. U.S. involvement escalated after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in August 1964 when North Vietnamese naval vessels reportedly fired on two U.S. destroyers. President Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnamese naval bases and Congress approved almost unanimously the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing the president "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the U.S. and to prevent further aggression."

In 1965, in response to stepped up military activity by the Communist Viet Cong in South Vietnam and their North Vietnamese allies, the United States began bombing North Vietnam, deployed large military forces, and entered into combat in South Vietnam. Requests from top U.S. military commanders in Vietnam led to the commitment of 485,000 troops by the end of 1967 and almost 535,000 by 30 June 1968. The casualty lists mounted as the number of troops and the intensity of fighting escalated.

Although he loyally supported administration policy, McNamara gradually became skeptical about whether the war could be won by deploying more troops to South Vietnam and intensifying the bombing of North Vietnam. He traveled to Vietnam many times to study the situation firsthand. He became increasingly reluctant to approve the large force increments requested by the military commanders. In early November 1967 McNamara's recommendation to freeze troop levels, stop bombing North Vietnam and for the US to hand over ground fighting to South Vietnam was outright rejected by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Largely as a result, on November 29 that year McNamara announced his pending resignation and that he will become president of the World Bank.